Ongoing Research

Stylometry Meets Transformer Embeddings

together with Levente Littvay – my mentor since my move to Budapest.

Political speeches, tweets, and press releases often come from a team of ghost‑writers. Stylometry—the science of measuring writing style —has long tried to unmask real authors, but the field is being revolutionized by large language models (LLMs). Can off‑the‑shelf embeddings of state-of-the art transformer LLMs sharpen our ability to assign (or dispute) authorship?

The first approach sticks to classics that any computational social science scholar can already run: sentiment dictionaries, TF–IDF with truncated SVD, and t-SNE plots. The second feeds exactly the same texts through progressively larger language-model encoders: domain-tuned BERT variants for English tweets, a nimble 7-billion-parameter Qwen that will run on a consumer GPU or an Apple-Silicon laptop, and a 72-billion-parameter edition that shows what “best possible” separation looks like. For every text we clusterize the embeddings into 2 or 3 groups, drop them into UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection, a learning technique for dimension reduction that came after t-SNE), and let k-means decide where the writing styles part company.

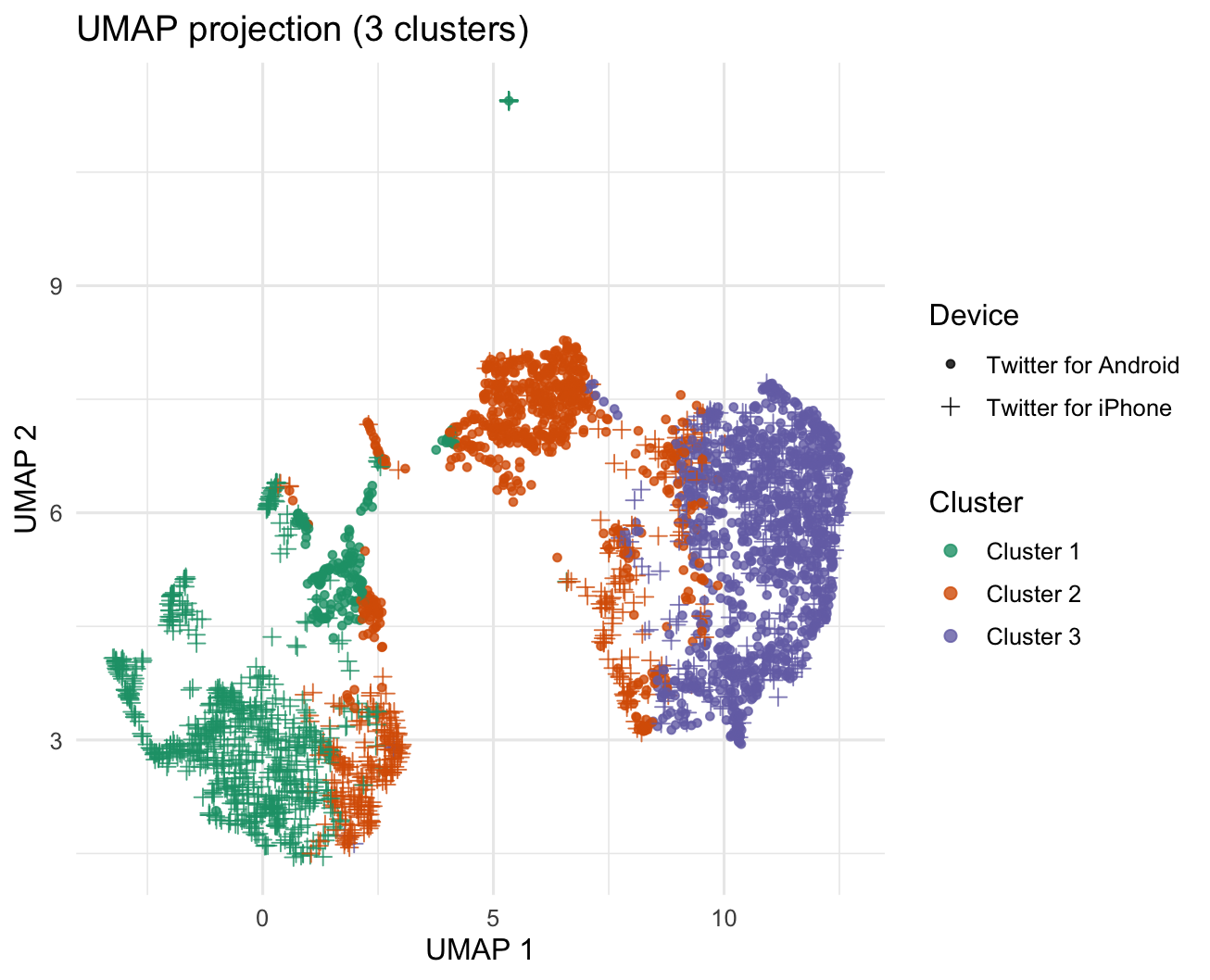

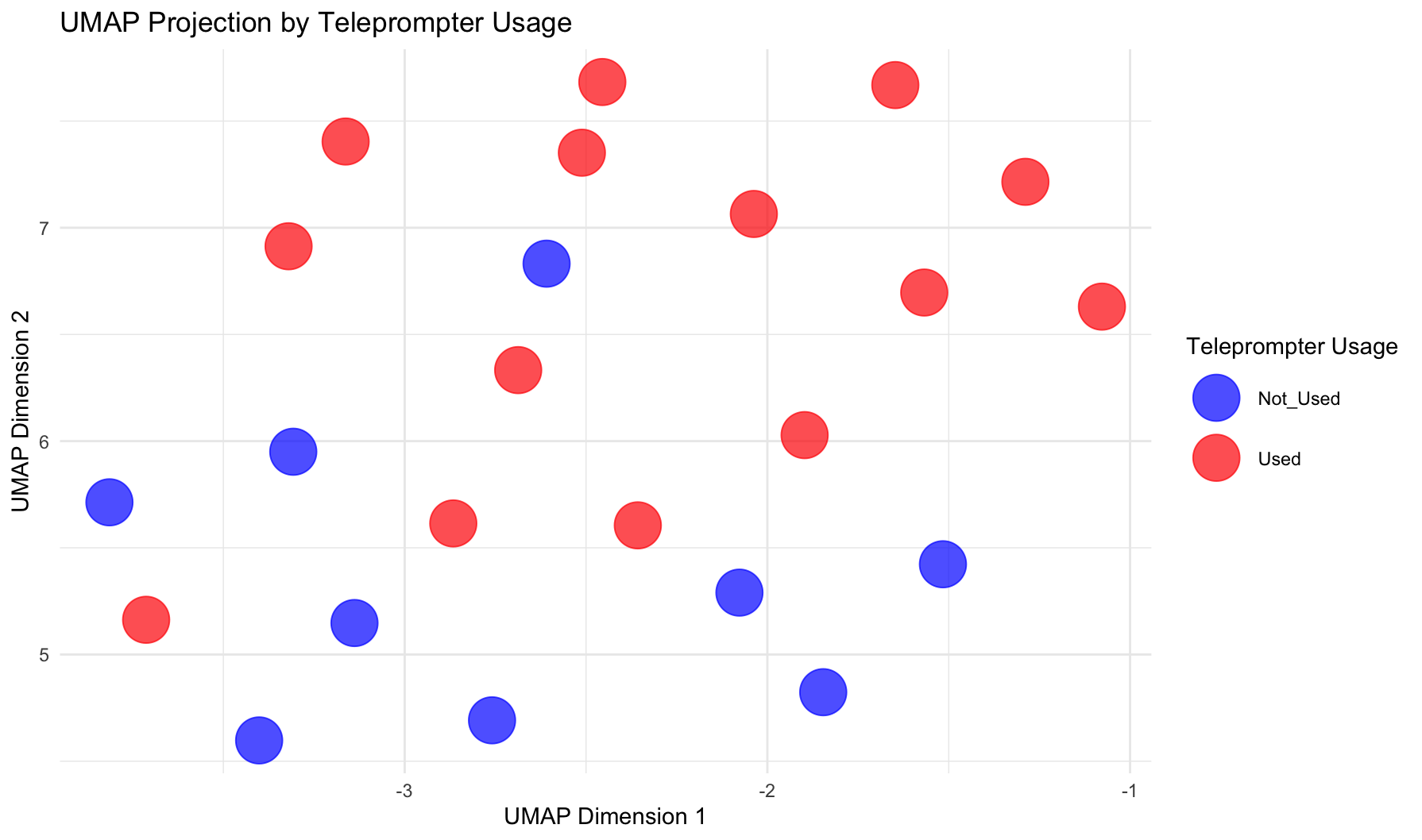

We validate the method on two ground-truth tasks: 3,800 Donald Trump’s Android-vs-iPhone tweets and 24 scripted-vs-impromptu speeches. While the two approaches both spot the authorial fingerprint, the embeddings draw cleaner, much more separated clusters, especially when the case gets more complicated. On a smaller number of much longer speeches, those dictionary counts collapse into noise, but even the mid-sized encoder keeps the scripted and improvised talks in largely distinct UMAP islands.

The purple island on the right is dominated by iPhone tweets, while the green island on the left is almost entirely Android. Embeddings separate devices more crisply, as opposed to dictionary features.

Figure 1. UMAP projection of tweet embeddings (Qwen 2.5 72B) clustered into three groups. Points are coloured by k‑means cluster (green = Cluster 1, orange = Cluster 2, purple = Cluster 3) and shaped by device (● Android, + iPhone).

Figure 1. UMAP projection of tweet embeddings (Qwen 2.5 72B) clustered into three groups. Points are coloured by k‑means cluster (green = Cluster 1, orange = Cluster 2, purple = Cluster 3) and shaped by device (● Android, + iPhone).

Figure 2. UMAP projection of speech embeddings (Roberta) clustered into two groups. Points are coloured by the usage of teleprompter (blue = Not Used, orange = Used).

Figure 2. UMAP projection of speech embeddings (Roberta) clustered into two groups. Points are coloured by the usage of teleprompter (blue = Not Used, orange = Used).

We then plan to apply our approach on 1000 Hungarian speeches by Viktor Orbán, where true authorship is unknown. By contrasting classic stylometry with progressively larger LLM encoders, we hope to see the speech writers.

(De-)politicization in authoritarian contexts: a state - civil society perspective

together with Francesca Chiarvesio – postdoctoral fellow at the University of Bern

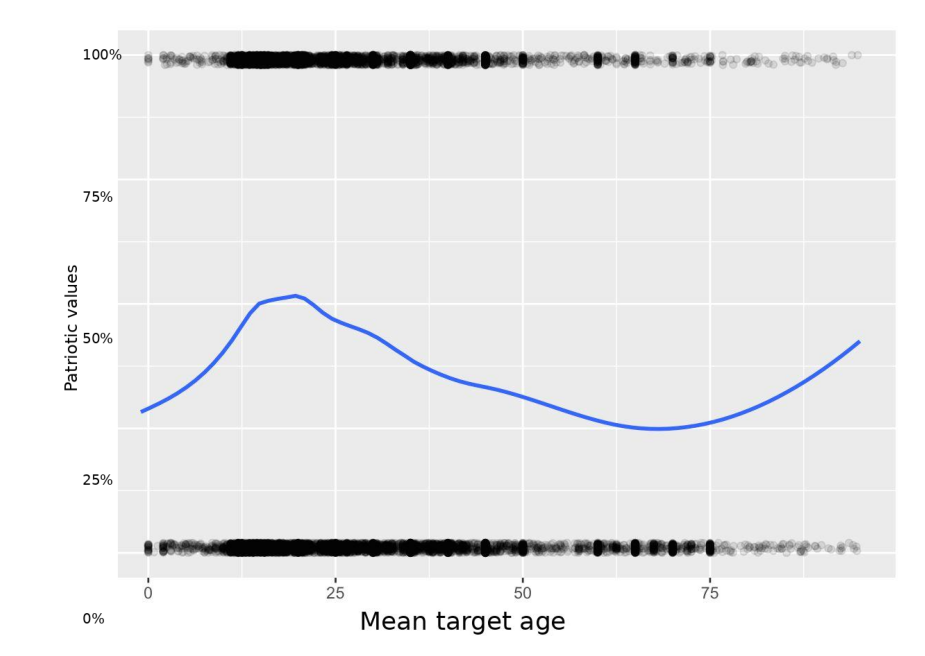

We are set out to understand whether Russia’s Presidential Grants programme rewards civil-society organisations (CSOs) for echoing the Kremlin’s conservative, patriotic rhetoric. We scraped roughly 150,000 project applications (successful and unsuccessful) submitted between 2017 and 2024, linked them to organisational data, and then used large-language-model coding plus fixed-effects logistic regression to see which factors actually predict who gets funded. Along the way we built novel scales, including a “patriotic-values” index and an estimated age of each project’s target group, to capture the ideological and demographic texture of CSO demands.

The headline finding upends a decade of conventional wisdom. Once we control for project quality, organisational experience and region, greater engagement with patriotic or traditionalist language does not improve, and sometimes even slightly hurts, an application’s chances of winning money. Instead, what matters most are performance-oriented signals: prior grant-management success, a credible web presence, modest funding requests, and—crucially—being based in so-called “new territories”, where grant flows surge as the state seeks quick legitimacy boosts. Even the post-2022 spike in CSO proposals to “indoctrinate” youth shows no corresponding bump in approvals; regime gatekeepers appear to value service delivery and reputational safety over overt ideological messaging.

These results suggest that what looks like depoliticisation from the outside is really a carefully managed politicisation of depoliticisation. By channelling thousands of small, topic-specific grants toward apolitical, short-term welfare projects, the Kremlin cultivates the image of an efficient, benevolent provider while cordoning off bottom-up mobilisation around contentious cleavages such as the war or socio-economic inequality. In other words, Russia’s authoritarian legitimation strategy relies less on cultural conservatism than on a performance-based welfare bargain—one that keeps civil society busy, visible and grateful, yet safely distanced from transformative politics.

This graph shows which target age (calculated from application content using aritificial intelligence) is more exposed to state ideology. Those are not yong children, but teenagers and students that are mostly exposed.

Do Terrorist Attacks Shift Parliamentary Rhetoric? Evidence from Germany Preliminary findings from an LLM assisted analysis

together with Gustavo Venturelli – Assistant Professor at the Stetson University

Conventional wisdom suggests that dramatic acts of violence, such is terrorism, push politicians toward tougher, often anti-immigration, positions. Yet systematic evidence for such rhetorical shifts remains thin. We set out to test the hypothesis in the German Bundestag: Do members of parliament (MPs) become more negative toward immigrants in the immediate aftermath of terrorist attacks?

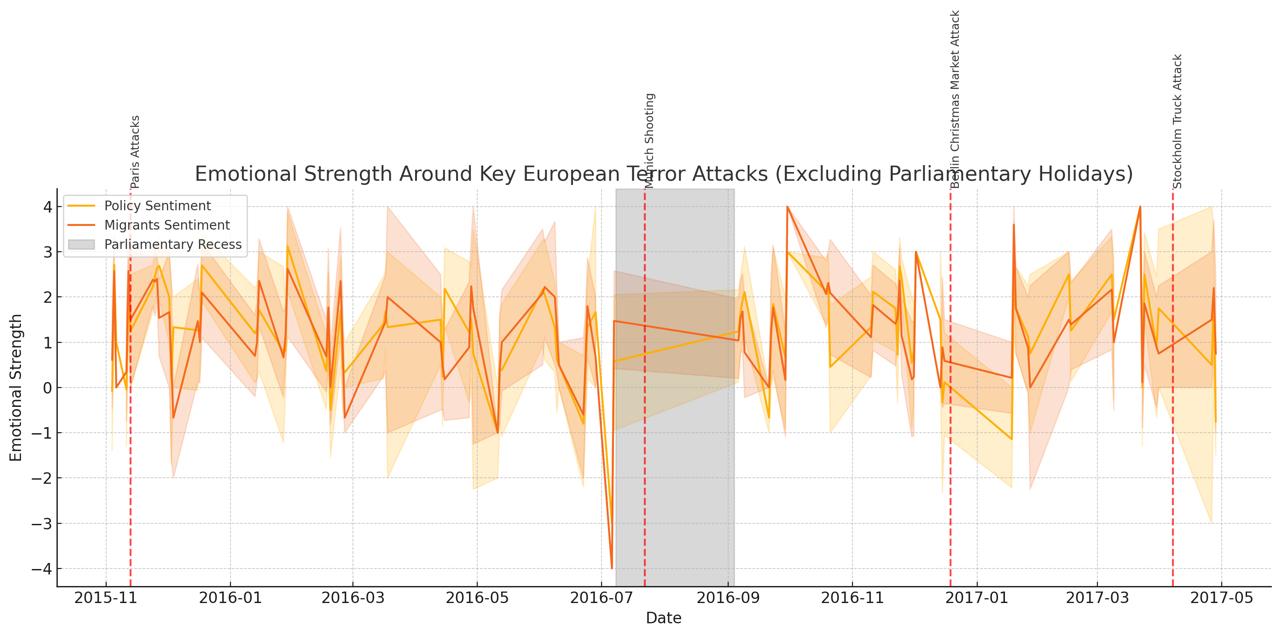

We used the corpus of roughly 250,000 speeches delivered in the Bundestag between 2014 and 2024. First, we analyzed every parliamentary speech using Large Language Models (LLMs). A lightweight LLM first marked any speech that mentioned migration. ChatGPT 4o was then used to distinguish between the evaluation of how the state handles migration policies and an emotion towards migrants per se. To isolate causal effects we ran a regression discontinuity in time design around four widely covered attacks between 2015 2019, using a ±30 day window atfer each event.

No statistically meaningful jump appears in either series. The figure below plots weekly averages with 95 % confidence bands; tone before and after each attack overlaps.

Figure: Weekly average emotional tone of Bundestag speeches that discuss migration policy (gold) and migrants themselves (orange). Shaded bands represent 9 % confidence intervals; vertical red dashed lines mark each terror attack. The grey rectangle shows the 2016 summer recess, illustrating how parliamentary holidays interrupt the time series.

In Germany, at least, parliamentary rhetoric on migration seems insulated from short term security shocks. Hovewer, one of our for attacks happened during the parliamentary holidays, and the other two in the neighbouring countries. The absence of effect can be caused by insifficient data.

If confirmed, the finding complicates the common narrative that terrorism automatically hardens elite attitudes toward immigrants. Instead, rhetorical responses may depend on parliamentary calendars, media framing, and the geography of violence. For scholars, the project showcases how off the shelf LLMs can open new frontiers in the systematic study of political speech.